When putting together a total training plan there should be a purpose in everything you include. We include dryland training in our swim program for several reasons: Improved durability, mobility, and agility, as well as increased energy-system fi tness. All are solid reasons to include dryland in our swim plan, but the two most important reasons we include dryland are to exploit the equations P=w/t (which we focus on in deck-based dryland) and F=ma (which we focus on in the weight room).

In order to improve our abilities in deck-based dryland (Power = work/time) we use time-based training as our mainstay. This works well for any team as the total time is defi ned with the time available for a specifi c training session (e.g. 45 min.). Our work and rest periods are then held to this time period within sets (e.g. 3 x 1:00 with 1:00 rest). Exercise sets are determined by both the exercises performed and main variables that are most needed by the team. We defi ne main variables as the exercises that we test (e.g. Squat-Thrusts, Sit-up Get-ups, Push-ups, etc), and you could also defi ne variables as general categories (Energy-System work = Squat-Thrusts, Strength = Pushups, etc). We chose to defi ne our variables as the exercises we test because it is imperative to have a metric against which to measure individual and team performances. So an average training set may end up looking something like:

3 x 1:00 Squat-Thrusts 1:00 rest

Goal = 30+ per 1:00

And our Test Set for that specific exercise is:

3 x 2:00 Squat-Thrusts 1:00 rest

Goals: Athletic = 60+ per, Elite = 75+ per

So for successful deck-based dryland we defi ne our total time available, we defi ne our exercises (what the team needs to work on most), we have a metric for some of these exercises (test set range), and we use primarily time-based training to improve our work amount in a given span of time (time-based set structure). Obviously, exercise selection is an important aspect since we want the most possible carry-over from general (dryland) to specifi c (swim performance). All of this to exploit P=w/t, improve our general power capabilities, and then specifi cally swim faster.

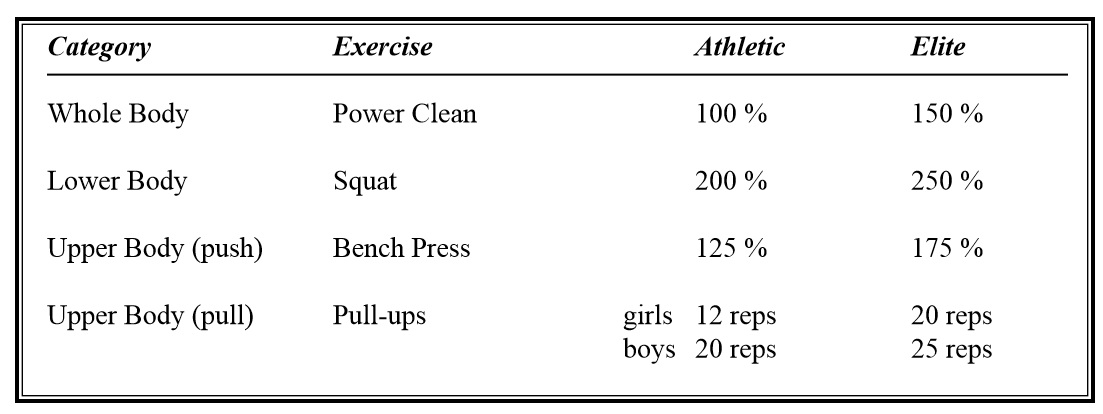

In order to improve our weight lifting abilities (Force = mass x acceleration) we use percentages of one-rep max (mass) and controlled speed (acceleration) to improve our strength levels (Force value). To set up a basic lifting plan, we use basic exercise categories (whole body, upper body, lower body) and then choose a number of exercises to fi ll these categories (e.g. whole body = Power Clean, Hang Clean, Deadlift, Clean & Jerk, etc). Included in this list of exercises are the specifi c exercises we test (whole = Power Clean, Lower = Squat, Upper (push) = Bench Press, Upper (pull) = Pull-ups (total #)). The progress we make in our tested lifts against our established metrics will determine our direction in the weight room most often. We choose to keep things simple and use certain percentages of body-weight as our goals for our tested lifts, as listed in the chart below:

In order to truly exploit F=ma we choose to use a relatively low-rep/high-set scheme. So an average training set might look like 10 x 3. This allows us to keep the weight relatively high (as to 1 rep max %) and allows us to keep our lifts fast (low rep sets = less energy-system fatigue). With speed and weight used as our main objectives within short sets, our unstated goal in the weight room is nervous-system efficiency.

Progressive resistance is the name of this game as well, so increasing intensity (primarily) and/or volume (secondarily) should progress at regular intervals. Total volume is controlled through total reps of a given lift (10 x 3 = 30 total reps, an average number of reps for our program) and intensity is controlled through percentages fi rst and through perceived effort second. Lifting speed is emphasized in most main exercises, and perceived effort of an athlete can also be evaluated by a coach looking at lifting speed with regard to percentage of weight of a given lift. If a certain percentage weight is moving much slower than expected, either the athlete is fatigued/not fully recovered, or they simply aren’t giving a full effort. And make no mistake, effort and consistency are of equal importance in progressive resistance, as in time-based training, and as in swimming itself.

This article provides a base template for your dryland training plan. In future articles we will go over specific session set-ups for deck-based dryland and lifting, including sequencing, mobility circuits, fi nishers, etc., as well as some tips and tricks to help you and your team along the way. You can get a head start on the competition by checking out our programs at www.FasterSwimming.com and you can browse our extensive video on our You Tube channel USAswimcoach.