About a year ago I read a very short but laudatory book review by George Block in the ASCA Newsletter. I promptly read Mindset by Stanford psychology professor Carol Dweck and was amazed at the immediacy of the new lens that Professor Dweck gave me for looking at the swimmers I coach. I sent the review to Carol, a friend from her days at the University of Illinois, and asked her if she’d write an article that introduced swim coaches to her ideas. This article, modifi ed from an article Carol wrote for Olympic Coach (V 21 #1 2009) and from Mindset, is the result of our collaboration:

Coaches are often frustrated and puzzled. They look back over their careers and realize that some of their most talented athletes—athletes who seemed to have everything-- never achieved success. Why? One answer as seen through Dweck’s lens is that they didn’t have the right mindset.

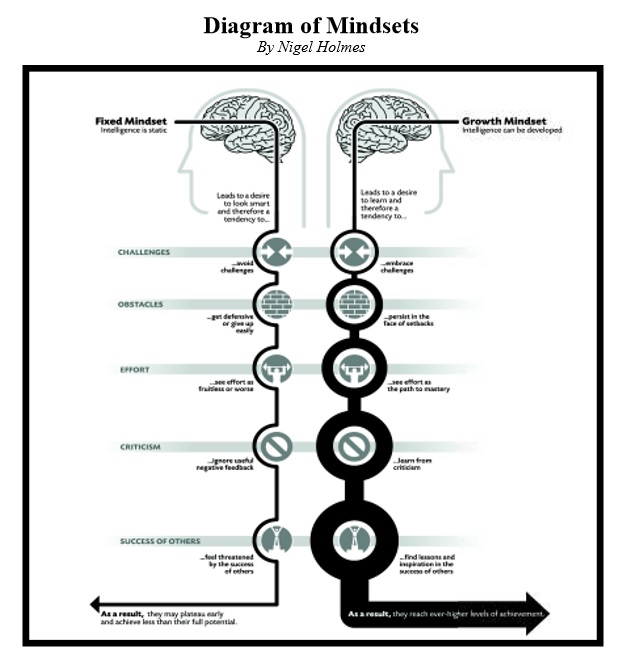

Dweck’s research identifies two mindsets that people can have about their talents and abilities: a fixed mindset and a growth mindset.

Those with a fixed mindset believe that their talents and abilities are simply fixed; they are born with a certain amount and that’s that. Swimmers with a fixed mindset who have a lot of natural talent may achieve great results early in their careers, without major effort, because of that natural talent. Being singled out as special and praised early on for their achievements can foster in them a sense that they will continue to be able to do well without the efforts that others have to make. This may be true, to a point. But with most of the swimmers who rely primarily on natural talent, there comes a time when they plateau. Since to that point they have always been special without having to sweat, struggle, and practice like other athletes, they may become so frustrated when they encounter obstacles or plateaus that they give up. The fixed mindset in these swimmers leads to the (false) belief that their natural talent will always keep them at the top of the heap. When they are not at the top of the heap, they experience so much shame that they often can’t bear to go on. They can’t give up their position of specialness, so they never progress to fulfill their potential.

Fixed mindsets in swimmers can show up in other ways as well. Coaches frequently find swimmers who, very early in their careers, define themselves by stroke and distance, e.g., “I’m a 100 fl y guy” or “I’m a breaststroker gal.” This is especially the case in high school and college swimming, where swimmers frequently carve out their niches as specialists. Some refuse to leave their niches, even when the process of learning other events can help them in their specialties or can lead them toward new successes. Frequently this occurs because engaging in new events may initially set them back to lower levels of success in terms of winning/losing and times. Like the “natural talent” swimmers, they are so afraid of losing their positions as “winners” such that they actually hold themselves back from improving.

Have you ever coached swimmers who felt that every race had to be their best swim or that they had to win every race? And when the swim wasn’t their best, or if they didn’t win, they were devastated? These are fixed mindset swimmers.

People with a growth mindset, on the other hand, think of talents and abilities as things they can develop—as potentials that come to fruition through effort, practice, and instruction. They don’t believe that everyone has the same potential or that anyone can be Natalie Coughlin, Dara Torres, or Michael Phelps. But they understand that even Natalie, Dara, and Michael wouldn’t be who they are without years of passionate and dedicated practice. In the growth mindset, talent is something you build on and develop. It is not something people are given and that stays constant. Growth mindset kids are the athletes who look at each swim with an eye toward analyzing what needs to be done, both in practice and in the next race, to improve on each performance.

Almost every exceptional athlete has had a growth mindset. Rather than resting on their talent, they constantly stretch themselves, analyze their performances, and address their weaknesses. Dara Torres has certainly defi ed myths about age through her training and dedication. Using new training methods that better suit her body’s needs as she grows older certainly points to her willingness to accept new challenges that keep her moving toward newly defined goals.

Dweck contends that research repeatedly shows that a growth mindset fosters a healthier attitude toward practice and learning, a hunger for feedback, a greater ability to deal with setbacks, and significantly better performance over time.

As coaches, we can use the Mindset lens as one of our tools for working with our swimmers. Obviously, the Mindset lens is not an exclusive tool, but it can help give powerful insights into what drives our athletes. Importantly, keep in mind that Dweck’s description of mindsets is a description of belief systems, and as such, they are able to change.

The belief behind the growth mindset, that talent can be developed, creates a passion for learning. Obviously, for racers, the ultimate measure of success is increased speed. But, working toward attaining speed is a continuous process because, no matter how fast swimmers race, they always want to go even faster. When racers define themselves with concrete characteristics …. “I can beat all of the people I race,” or “I am a 00:48 hundred free swimmer,” they define themselves in a fixed-mindset mode: by “product” rather than by “process.”

In the growth mindset, we ask,

- “Why waste time proving over and over how great you are when you could be getting better?”

- “Why hide deficiencies instead of overcoming them?”

- “Why look for teams/coaches who shore up the self-esteem that you have derived from your talent instead of looking for training environments that

will challenge you to grow?” - “Why seek out the tried and true instead of experiencing that which will stretch you?”

The passion that swimmers have for stretching their abilities and finding value in the effort of doing so, even (or especially) when their races are not going well, is the hallmark of the growth mindset. This is the mindset that allows people to thrive and grow during some of the most challenging times in their lives.

How many times have you heard freestylers say, “My kick sucks?” Do they resign themselves to this statement because kicking is unrewarding, they hate it, and consequently rely on arm power, or do they challenge themselves to develop a stronger kick?

How do the mindsets work and what can coaches do to promote a growth mindset?

Before addressing these issues, let us first answer some other questions that are often asked about mindsets.

Questions About The Mindsets

Which mindset is correct?

Although abilities are always a product of nature and nurture, a great deal of exciting work is emerging in support of the growth mindset. New work in psychology and neuroscience is demonstrating the tremendous plasticity of the brain—its capacity to change and even reorganize itself when people put serious labor into developing a set of skills. Other groundbreaking work (for example, by Anders Ericsson, et. al (1993)) is showing that in virtually every field—sports, science, the arts—only one thing seems to distinguish the people we later call geniuses from their other talented peers. This one thing is called deliberate practice; or, as Robert Sternberg (2005) explains, the major factor in whether people achieve expertise “is not some fixed prior ability, but purposeful engagement.”

Are people’s mindsets related to their level of ability in the area?

No, at least not at first. People with all levels of ability can hold either mindset, but over time those with the growth mindset appear to gain the advantage and begin to outperform their peers with a fixed mindset.

Are mindsets fixed or can they be changed?

Mindsets can be fairly stable, but they are beliefs, and beliefs can be changed.

How Do The Mindsets Work? The Mindset Rules

The two mindsets work by creating entire psychological worlds, and each world operates by different rules.

Rule #1

In a fixed mindset, the cardinal rule is: Look talented at all costs. Jealously guard that talent.

In a growth mindset, the cardinal rule is: Learn, learn, learn! Take risks. We may even want to cite Ms. Frizzle, of PBS’s The Magic School Bus, who frequently exhorts her students, “Take Chances, Make Mistakes, Get Messy.”

In Dweck’s work with adolescents and college students, those with a fixed mindset say, “The main thing I want when I do my school work is to show how good I am at it.” When given a choice between a challenging task from which they can learn and a task that will make them look smart, most of them choose to look smart. Because they believe that their intelligence is fixed and that they have only a certain amount, they have to look good at all times in order to maintain their and others’ view of who they are.

Those with a growth mindset, on the other hand, say “It’s much more important for me to learn things in my classes than it is to get the best grades.” They care about grades, just as athletes care about winning, but they care first and foremost about learning. As a group, these are the students who end up earning higher grades, even when they may not have had greater aptitude originally.

- What happens when you ask swimmers to race new events or to change their technique? Are they fearful of looking bad, or do they see it as an adventure or a new challenge?

- Several years ago, my daughter plateaued in her chosen college events, 50 and 100 yd butterfly, and she was getting very frustrated. I suggested that she play with the 400 IM, and she grimaced. Then I, a confirmed masters freestyle sprinter, made the challenge: “If you race the 400 IM, so will I, and I’ll even add the 200 fly to up the ante.” She had the best season of her long swim career, and I celebrated my 65th birthday at the Illinois State Masters Meet with a whole new set of challenges and exciting horizons in swimming. My first goal was to race the 200 fly “with dignity.” Better times are next on my list. It’s never too late to accept a new challenge.

Dweck’s studies show that, precisely because of their focus on learning, growth mindset students end up with higher performance. They take charge of the learning process. For example, they study more deeply, manage their time better, and keep up their motivation. If they do poorly at first, they find out why and fix it.

Dweck has also found that mindsets play a key role in how students adjust when they are facing major transitions. Do they try to take advantage of all the resources and instruction available, or do they try to act as though they don’t care or already know it all? In a study of students entering an elite university, Carol found that students with a fixed mindset preferred to hide their deficiencies rather than take an opportunity to remedy them—even when the deficiency put their future success at risk. In swimming, the prospect of changing technique can be very threatening to a fixed-mindset athlete, since these changes frequently result in slower times for a while. Witness Michael Phelps’ giving straight-arm freestyle a try. Or Dara Torres learning a “new” freestyle when she returned to competitive swimming.

Look at age groupers who are great at the 50-yard races and then fade in their 100s and 200s. Some of these kids are reluctant to take on the challenge of learning to swim the longer races. They know that they probably won’t be consistent winners when they begin to compete at longer races and that they will, consequently, reveal to the world that they aren’t the swimmer who is constantly a winner. Others gladly take the challenge, partly because it’s fun and partly because it’s rewarding to see themselves getting better.

Rule #2

In a fixed mindset, the second rule is: I don’t need to work so hard or practice too much because my talent will get me good results.

In a growth mindset, the rule is: Work with passion and dedication—effort is the key.

- We have all heard stories of really fast high school swimmers who quit their college programs because they did not want to notch up their workload to remain competitive at the collegiate level. In high school, these swimmers tend to rely on talent, but when they reach college, everyone is talented and harder work is needed to remain competitive. Like the “natural talent” swimmers, they are so afraid of losing their positions as “winners” such that they actually hold themselves back from improving.

- Woven into Rule #2 is the “Fear of Failure.” Those athletes with a lot of talent sometimes do not try for fear of failing. They do not put forth the maximum effort, or they self-sabotage because they are afraid: if they give it their all and “fail,” their weaknesses will truly show. If they don’t give it their all, then they can always excuse themselves.

- One of our nine-year-olds qualified with the second-fastest time for the finals in a prelim/final meet. He refused to swim in the finals because “I can’t beat the guy who qualified first, so what’s the point.”

- One high school coach discussed her experience with a top age-group distance swimmer who entered this coach’s high school program: “Her technique needed a major overhaul, and she refused to make any sincere effort to change anything. One day when confronted with a challenge to alter her head position through the turns for the 500 free, she burst into tears, ‘Everyone is always trying to change my turns, and they all want me to do something different. I’m tired of it; it always makes me slower!’ She spent a lot of time at the trainer getting ice on her shoulders and left high school with little change in the times or technique she brought to high school four years earlier.”

Those with a growth mindset know that they have to work hard, and they are willing to do it. They understand that effort is what ignites their ability and causes it to grow over time.

Carol gets letters from former child prodigies in many fields. They were led to expect that, because of their talent, success would automatically come their way. It didn’t. In the world of Olympic sports, we do not do our young athletes a favor by allowing them to believe that great talent alone will transport them to the medal stand. From recent research, we fnd that the really talented athletes spend at least 10,000 hours of guided practice, or, as Ericsson and his colleagues (1993) describe 10 years of “deliberate practice” to reach their high levels of achievement.

Recently Carol conducted a small study of college soccer players. She found that the more a player believed that athletic ability was a result of effort and practice rather than just natural ability the better that player performed over the next season. What these players believed about their coaches’ values was even more important. The athletes who believed that their coaches prized effort and practice over natural ability were even more likely to have a superior season.

What coaches can do:

- Encourage athletes to do skills, drills, and sets that they are not comfortable doing. It may be especially important to make your best athletes practice skills they are not very good at or do not like doing, all in an effort to show the importance of learning both to these swimmers and to the other swimmers on the team who look up to these fast performers.

Rule #3

In a fixed mindset the rule is: When faced with setbacks make excuses, blame others, blame your fragile shoulders/knees, blame your coach, or conceal your deficiencies.

In a growth mindset the rule is: Embrace your mistakes, confront your deficiencies, and seek help to understand and overcome them.

- “Failure is feedback.” Billie Jean King http://www.dailycelebrations.com/failure.htm

Carol has found over and over that a fixed mindset does not give people a good way to recover from setbacks. After a failure, fixed-mindset students say things like “I’d spend less time on this subject from now on,” or “I would try to cheat on the next test.” They make excuses, they blame others, and they make themselves feel better by looking down on those who have done worse. They do everything but face the setback and learn from it.

- Sometimes we see adolescent swimmers blaming their over-trained shoulder or knee joints as an excuse to “escape” from hard training. The real task for many of these kids is to re-tool their stroke technique and reconfigure their primary events to suit their maturing bodies. For many, this is an exciting prospect, and for others, it is a daunting task to be avoided. In this situation, we have two growth issues: physical and mindset.

- Sometimes the fastest/most talented swimmer is not the hardest worker, and this swimmer becomes the other swimmers’ role model. Frequently these “role model” swimmers get leadership roles (e.g., captain) because they are the fastest swimmers. When these fixed mindset leaders become team leaders, they frequently come in conflict with the coaches’ values and don’t turn out to be adequate leaders.

What coaches can do:

- In most racing situations, swimmers focus on times, and age group swimmers frequently focus on their times as compared to friends’ and competitors’ times. Rather than encouraging your swimmers to focus on times as the only criteria of racing success, why not give race assignments that encourage other areas of development… "let’s focus on good turns….no breathing for four strokes into each turn, come out with 5 undulations, and no breathing for the first four strokes;” “let’s focus on good rotation and long reach with an early catch.” At the end of the race, then, coaches and swimmers have things to discuss that invite further action….process oriented actions…instead of ultimate “succeed or fail” goals (times).

- Most high school coaches have a relatively short season with a high number of meets. In our 14-week fall high school girls’ season, our team usually has around 13 meets, ranging from duals to multi-team invites. Swimming in meets is how we practice to swim in meets. If swimmers are to learn to become better racers, coaches have to consider “allowing” their athletes to take risks with new techniques and race strategies. In these situations, the reward isn’t necessarily a faster time. These situations are learning possibilities. For example, coaches might suggest:

- “How about taking your 100 free out at the same speed as your 50 free and see if you can maintain that speed for your second 50? You may die, but you may not. You’ll never know unless you take the chance. If you do die, we’ll see where it happens, and we’ll modify your training to work on that part of your race.”

- “Now is the time to practice that new breathing technique we’ve been working on. You may have to do more thinking about technique during your race than you are used to, but let’s give it a try and see what happens.”

In a TV interview after prelims, the commentator asked Michael Phelps, “What are you going to do in the finals, just swim faster?” Michael responded, no, that was not his strategy. He still had technical adjustments to make in his coming race.

How Are Mindsets Communicated?

Mindsets can be taught by the way we praise. In many studies, Carol has found a very surprising result. Praising children’s or adolescents’ intelligence or talent puts them into a fixed mindset with all of its defensiveness and vulnerability. Instead of instilling confidence, it tells them that we can read their intelligence or talent from their performance and that this IS what we value them for. After praising their intelligence or talent, Carol found that students wanted a safe, easy task, not a challenging one from which they could learn. They didn’t want to risk their “gifted” label. Then, after a series of difficult problems, they lost their confidence and enjoyment, their performance plummeted, and almost 40% of them later lied about their scores.

What should we praise?

Carol found that praising students’ effort or strategies (the process they engaged in, the way they did something) put students into a growth mindset in which they sought and enjoyed challenges and remained highly motivated, even after prolonged diffi culty. Thus, coaches might do well to focus their athletes on the process of learning and improvement and to remove the emphasis usually placed on natural talent. A focus on learning and improvement tells athletes not only what they did to bring about their success, but also what they can do to recover from setbacks. A focus on talent does not.

Giving praise that is meant to boost self-esteem, at the expense of honesty, can also have negative results in terms of fostering growth mindset and success outcomes. A growth mindset coach will talk about effort and commitment. When a swimmer didn’t place as highly in an important meet as she had expected, Coach explained, “You weren’t the best, today. Your swimming shows that you’re working hard, but you need better technique and better conditioning to swim faster. Those are things that you can work on.”

What coaches can do to create a process focus:

- Swimming fast is the result of putting multiple components together. Coaches are very nicely situated to highlight the process of putting together strategies that help the swimmer achieve new goals. Coaches can, for instance, outline the components of a race and then involve their swimmers in putting together new strategies to integrate these components into their races. In this way, we help take our athletes from old habits that keep them static (but comfortable), to new pathways toward improvement. And, in this process, coaches model a growth mindset. How, for instance, will a new head position and altered breathing patterns smooth out stroke mechanics? Many coaches ask swimmers to keep journals that analyze their meets and practices and then include plans for how to get better.

- On a “growth-oriented” meet day, coaches may have pre-race consultations that focus on helping swimmers to think about things that they CAN do. Since race times are a function of properly “doing” things that are under swimmers’ control -- proper body alignment, cadence, turns, etc -- swimmers can work toward executing sub-goals with the ultimate goal of faster times -- paying attention to head position, good rotation, early catch, etc. After the race, the coach can then talk about how well swimmers swam their races in terms of executing these components, and then talk about strategies for building on those changes.

- When time permits, right after races coaches may want to ask their swimmers for their race analysis before giving coach feedback. Coach: “Talk to me about your race. What did you like about what you did? What didn’t happen the way you think it should have? What do you propose we do to capitalize on what you did well, and what should we do to improve what you didn’t do well?” If a swimmer answers, “I felt good,” the coach may want to probe, “What about your swimming felt good? Let’s capture that feeling and translate it into continued swims.” Or, Swimmer: “I missed my turn.” Coach: “What parts of your turn weren’t on the mark? What should you practice in order to make your race turns better?”

- Doing push-ups for having taken breaths out of turns is a punishment, not a growth-oriented coaching strategy. Having the athlete practice turns without breathing is a more appropriate and effective growth-oriented strategy.

- One of the more diffi cult facets of racing is confronting and moving through pain, which is a natural part of high-level swimming. (Note: Here, we are talking about pain that results from exertion/fatigue, not injury-related pain.) Helping swimmers learn to confront and move through pain promotes tremendous growth. We frequently see kids simply stopping when it hurts. They think that when it hurts they have reached their limits of performance. Helping them learn to confront and work with pain is a totally challenging growth experience. In a particularly exhausting high school challenge set, one of our captains was obviously in pain. After the set she described to one of the freshman sprinters about how confronting this pain was a necessary challenge. The freshman wrinkled her face and completely rejected this concept. For the next four years, her quietly executed bathroom breaks tended to occur when the sprint workouts entered the pain phase. She maintained her status as one of our faster sprinters, but she really didn’t get much faster and reach toward her full potential as a swimmer.

- In this kind of confrontation with an unsavory aspect of training, coaches may consider talking with their swimmers about the kinds of workouts where confronting pain and working through it is, in fact, a major object of that workout. From Mark Shubert: The pain you feel in practice is similar to the pain you will feel in a race. In each race, a point comes where you either defeat the pain, or you give in to it. Practice is your time to practice defeating that pain.

- Labeling swimmers as wimps when they shy away from pain merely reinforces the fixed mindset view that some swimmers can work through pain and some cannot. In the growth mindset, our mission is to figure out ways to help athletes meet this challenge.

- Coach: “You can only grow and get faster in several ways…better technique, better conditioning, better attitude. Today we are working on confronting pain. You may not like it, but you have to work through it in order to get faster.”

- This season I used some great hints that Frank Bush gave at the 2009 Central States Swim Clinic. I think that these hints can serve as a model for coaches to help fixed mindset swimmers transition to a growth-oriented perspective. I coach girls’ high school swimming for a team that typically has 16 members, few of whom are year-round club swimmers. One of the 13-year-old swimmers began the season as a self-proclaimed breaststroker whose technique needed major tweaking. As well, she had little faith in her 100 yard, 1:07 freestyle. I proposed some major technique changes in both strokes, and, after trying out these changes she was very discouraged. These changes didn’t feel right, and she was swimming slower. I took a phrase from Bush, “If you don’t believe in these changes, hop onto my beliefs that they’ll work for you over time.” Eight weeks later, and with big smiles, she took 3 seconds off her 100 yard breast, and 6 seconds off her 100-yard free. I’m certain that her hopping onto my mind-set played a major role in helping her believe in the process that helped her make the changes she needed.

- I also took a leap in response to Dave Salo’s talk at that same Clinic. Basically, Salo outlined a training strategy that fl ew in the face of all of the conventional models I have been taught. Instead of constructing workouts based on a highly structured energy-system model, Salo proposed a strategy that introduced lots of non-swimming-butin-the-water activities that put fun and novelty into the equation. He still worked the energy systems, but without exclusively using the standard swimrest-swim-rest format. I rationalized that, since I coach at the University of Illinois Laboratory High School where trying out new educational methods is part of our charge, what the heck. We experienced at least as many PRs this year as in past years, as well as 76% PRs at our championship meet. Perhaps best of all, the girls have big smiles at our 5:30 AM practices. I think that Coach DeMont (2001) who wrote the following paragraph could easily conceptualize this situation in a Mindset framework: ”Many swimmers hang on to their old ways as if those habits were their lifeblood. The idea of trying to integrate something new into their stroke scares them. This kind of swimmer would rather remain a national qualifi er than risk going through the process of change that could possibly land him or her in a place in the fi nals. A change in technique requires repetition of the new task until it becomes habit. As a coach, I sometimes have to ask, ‘Do you want to move to the next level or remain the same?’ In my eyes, four hours a day or more is too much time to spend to protect "qualifi er" status. Go on, take a risk! “

- Coaches can identify their fi xed mindset athletes by asking them to agree or disagree with statements like this:

- “You have a certain level of athletic ability, and you cannot really do much to change that;”

- “Your core athletic ability cannot really be changed;”

- “You can learn new things, but you can't really change your basic athletic ability.”

- They can also ask their athletes to complete this equation: Athletic ability is ____% natural talent and ____% effort/practice. This exercise may be tough for many swimmers; they see other kids who seem to always be faster and who seem to swim effortlessly. “Obviously, these other kids swim fast because they have talent.”

- I think the language that our swimmers use gives strong hints as to where they stand: Do we see differences between swimmers who say “I can’t” (a very fixed position) and those who say “I’m having trouble with this…..” (a very growth oriented position). People have a much easier time moving forward from “I’m having trouble…” since this kind of thinking invites a solution to pursue. “I can’t….” indicates an attitude of helplessness and indicates the perspective that effort is not a solution.

With these kinds of hints coaches can work on fostering growth mindsets in their athletes who place an undue emphasis on fixed ability.

Swimmers’ Relating to Coaches:

In relating to his/her coach, we may see fixed mindset swimmers:

- Wanting to be put on a pedestal;

- Expecting to be the favorite because his/her times are the fastest;

- Wanting to be made to feel perfect and/or special;

- Having a very public tantrum after a disappointing race and expecting the coach’s sympathy.

A growth mindset swimmer might want a different relationship with the coach:

- Wanting weaknesses to be seen and wanting the coach to help the swimmer to work on thes problems;

- Wanting to be challenged to become better;

- Wanting coach to offer encouragement to learn new things.

What About Coaches’ Mindsets?

Fixed mindset coaches may convey to their teams that natural talent is valued above all. When a coach has a fi xed mindset, athletes will be eager to impress the coach with their talent and will vie to be the superstar in the coaches’ eyes. One unintentional possible scenario of this coach mindset is the creation of unhealthy rivalries between swimmers who are vying to be the superstar.

On the other hand, growth mindset coaches are more likely to foster teamwork and team spirit. If athletes know that their coach values passion, learning, and improvement, players can work on these things with each other and with their coaches to produce improvement. In this scenario, healthy rivalries may develop where swimmers encourage each other to mutual success.

- At swim camp one of the kids told this story: Her workout group of 13 year olds came to practice in a very unruly, goofy mood and wouldn’t pay attention to the coach as he tried to start the practice. From complete frustration with their inattentiveness, he quietly walked to the chalk board and wrote, “5000 meters butterfl y.” In my thinking, 5000 fl y is out of bounds for age groupers, let alone seasoned swimmers, and, in fact, did 5000 fl y address the issue? In Mindset Carol discusses the legendary basketball coach, John Wooden: “He did not tolerate coasting. If the players were coasting during practice, he turned out the lights and left: ‘Gentlemen, practice is over.’ They had lost their opportunity to become better that day.” (p. 207) What would have happened if this swim coach had done the same thing?

- I was working on streamlining off the wall with a group of energetic 8-12 year-olds. I asked them to push off on their sides, hold that posture as

far as it would take them, and then stand up for my feedback. Most of them surfaced, bounced around, and headed back to the wall without paying attention to the feedback that I was giving. I fi gured that I would work with those who paid attention and let the others bounce. But one bouncer came back to the wall and said, “I need you to tell me what I did wrong. How can I get any better unless I know what I need to work on?” Light bulb moment. I’m the adult, and it’s my job to fi gure how to work with these kids, especially an incipient growth-mindset kid. So, we changed the routine. Push off, streamline, return to the wall, and get your feedback face to face with me. The feedback wasn’t as immediate as I had planned, but it stopped me from yelling to get their attention. Let them bounce if their energy levels and joy of the water dictate bouncing. It worked.

In Game On, Tom Farley (2008) discusses youth sports coaches: “There are more than seven million youth and high school coaches in the U.S., and very few have received any form of training, even if it’s just a three-day course on skills and drills. And even fewer have been taught how to coach for character. So most of them wing it, using disciplinary techniques that experts say aren’t developmentally appropriate for elementary and middle-school kids: extra exercise (64 percent), verbal scolding (42 percent), public embarrassment (18 percent), suspension (8 percent), and striking or hitting (2 percent) according to survey results presented to the American College of Sports Medicine in 2006” (p. 195).

None of these disciplinary techniques encourage growth through meeting challenges. Although I’m not sure if any research supports my intuition, I’d venture that coaching styles that rely on punitive actions don’t engender the kind of joy and inquisitiveness for exploring newness that growth mindset athletes thrive on.

I would also venture that fi xed mindset coaches may be intolerant of feedback from others since these coaches may see feedback as impugning their own ability. These coaches tend to see themselves as the ultimate swimming authority in the lives of the kids they coach. The fi xed stance they take, “my way or the highway,” negates their ability to grow as coaches and to process new information that may help them improve the quality of work that they can accomplish with their charges.

How can coaches work with parents?

Where kids get their mindsets is not a clear issue. They probably develop their belief systems from many places: peers, teachers, coaches, parents. Let’s be totally clear: parents are not the enemy. From their perspective, they are acting on their kids’ behalves, and most parents only want what is best for their children. But many parents bring their personal issues into their kids’ lives. Many parents may come from a fi xed-mindset perspective themselves and can’t help but apply a fi xed mindset to their kids’ swimming endeavors.

From the coach’s point of view fi xed mindset parents are frequently the bane of the age-group world, the high school world, and, surprisingly, the college world, as well. Since parents are a strong given, and, in fact, the real foundation of youth sports, we must learn to incorporate them into their kids’ athletic endeavors in ways that are consistent with their kids’ healthy development. In other words, we may need to help our athletes’ parents switch to a growth mindset as well. Our job is to make our position clear and to negotiate a mutual support system between coaches and parents for the benefi t of our athletes.

- Last summer, our four-day technique camp ended with Sports-a-Rama: water basketball, inner tube races, funny dives, and the like. One of our 11 year-olds was quickly ejected from his tube in the inner tube fi ght and emerged from the pool in inconsolable tears that lasted for quite a while. This lad is a very successful age-group swimmer. He usually wins races, and he has good technique. But, winning is a family value. A few days later, the same boy and some of his teammates were working on turns with a coach who is really great with their age group. Mom was watching. The kids were laughing and having fun as they also drilled their turns. In one instance, the coach said, “Now, let’s try this turn again keeping in mind what we’ve just learned.” And mom yells to son, “And do it perfectly!!!!” No wonder the kid cries when he doesn’t win an inner tube fi ght. His winning (“perfection”) defi nes his self image, and anything less is failure.

- On the first day of a two day, multi-event meet, one of our fast 9 year-olds fi nished his fi rst race and announced that he didn’t feel very fast that day. He decided that he would scratch the rest of his races. Apparently, putting out the effort to swim well when he felt that he couldn’t swim his fastest wasn’t part of his mindset. He comes from a family where swimming fast and winning defi nes all of their age-group swimmers.

- At several age-group meets, one of our 16 yearolds ended many of her races in tears saying, “My parents are going to hate me.” Why? “Because I didn’t have a cut time/best time.” In a conversation with Mom, she explained to me that she demanded of each of her kids that they pick an endeavor, music or sports, and excel in this choice. With swimming, best times and cut times were convenient markers of excellence for Mom. Mom really didn’t know much about swimming, but she did know how to operate a stop watch and read spread sheets.

So, what could these parents have done in a growth-oriented direction?

Consider this model as a starting place: In the fi xed mindset, everything is about the outcome. If you’re not the best, it’s all been wasted. The growth mindset allows people to value what they have done, regardless of the outcome. Using this paradigm, parents should refrain from praising only outcomes and focus on the components of their kid’s performances that led to these outcomes. Sure, you want to praise a personal best time, but you shouldn’t be defi ning your child by this time. “You looked like you were working really hard. All of the time that you put into practice seems to be paying off.” NOT, “You are a really fast swimmer, and it really looked that way today.”

In a fi xed mindset, parents and coaches label: E.g., “You are a fast/talented swimmer.” If being a “fast swimmer,” is good, then a slow race means that you are bad and that you failed. In a growth mindset, a sub-par performance can be transformed into a learning experience. “What were the parts that didn’t work today, and what can we work on in practice this

week?”

- When coaches and parents hear, “I can’t” or “I failed,” we need to help our athletes change their language, and consequently, their mindset. Rather than, “I can’t,” we should encourage “I’m having trouble with XYZ, can you help me with it?” Or, we may hear, “I’m bad at this,” (fi xed) versus “I did or didn’t do…” (growth). Coaches and parents need to recognize these differences so they can have their kids learn to reframe their analyses immediately. So, if athletes say “I sucked,” the coach can say “What are the parts of your race that sucked? I know you’re disappointed. Let’s see what we need to work on for the next race.”

A fixed mindset approach is destructive and contributes to feelings of being judged: “win, win, win -- prove yourself -- everything depends on it.”

A growth mindset approach is constructive and encourages “observe, learn, improve, become a better athlete” with the parents’/coaches’ roles as being that of helpers who foster a growth process that guides athletes toward getting better.

For coaches and parents:

- Don’t over-praise intelligence and/or talent, and don’t only praise results.

- Do praise the effort and what athletes accomplish through practice, persistence, and good strategies.

- Talk with your athletes about their work in a way that admires and appreciates their efforts and choices. “In practice you really worked hard on your transitions, and your race showed it.”

- Focus on what your swimmers/children can control. Athletes never have complete control over winning They certainly can control what they do, but they can’t control what their opponents will do.

- We should not assume that swimmers have the ability to do the kind of self- analysis necessary to identify their mindsets, and their everyday personality may block this kind of objectivity. Mindsets must be established with the help of coaches, parents, or others who are highly infl uential in the lives of young people, athletes, or others. Without help, we should not expect our kids to do it themselves. Coaches who believe in mindset development must dedicate time away from training to work on it.

One thing I always like to see is that the kids I coach are having fun. If they are enjoying what they are doing, they are usually learning and having a good experience. I also like to engender their ownership of their actions. I want them to be swimming and working hard because they see an internalized value in doing so, not because I (coach) or others (peers/parents) want them to be doing this.

Conclusion

Mindsets are beliefs. Beliefs can be changed.

- Praising ability usually results in decreased performance levels;

- Praising effort usually results in increased performance.

At the level of the swimmer, a growth mindset allows each individual

- to embrace learning;

- to welcome challenges, mistakes, and feedback;

- to understand the role of effort in creating talent;

- to accept that growth is change and change involves risk.

At the organizational level, a growth mindset is fostered

- when coaching staffs present athletic skills as acquirable;

- when passion, effort, improvement, and teamwork, not simply natural talent or results, are valued.

Growth mindset coaches

- are mentors and not just talent judges;

- inspire and promote development no matter what the natural talent may be;

- nurture a new generation full of athletes who love their sport and bring it to the highest level.

Growth mindset parents

- encourage their kids to take risks that engender growth;

- love their kids independently of their performance outcomes;

- support their kids through periods of frustration and disappointment.

Futurist and creator of the Geodesic Dome, Buckminster Fuller, articulates an educator’s view of growth mindset:

“If I ran a school, I'd give the average grade to the ones who gave me all the right answers, for being good parrots. I'd give the top grades to those who made a lot of mistakes and told me about them, and then told me what they learned from them.” http://www.dailygood.org/pdf/dg.php?qid=3054

The final paragraphs of Lynn Cox’s (2004) book, Swimming to Antarctica, beautifully articulates a great athlete’s growth mindset:

“I gave a lecture to a group of elementary and high school teenagers in Callaway, Nebraska, and was asked countless questions about the Antarctica swim and my other swims before it. One of the questions that made me pause was from a seven-year-old boy. He asked, “If you had a goal and worked very, very hard toward it, but you didn’t accomplish it, would you still be happy?” I wondered what kind of goal a seven-year-old could have worked so hard toward and not achieved, and how such a young boy could have such a profound question.

I answered him as best I could: “I would have been happy that I tried to reach my goal, but if I didn’t succeed, I would want to go back and fi gure out what I thought I needed to do to accomplish it, and then try again.”He smiled and nodded: he appeared to understand so much beyond his years. I still wonder about him and if what I told him was helpful. One friend said I should have told him to reevaluate his goals and to lower the bar if the goal was too high. I asked myself if I would follow that advice, and I decided that’s not the way I do things. I don’t lower the bar. Maybe it’s because the bar’s not high enough or maybe it’s because I work toward goals in reachable steps. The swim to Antarctica was the culmination of thirty years of swimming and two years of complete focus on one big goal. Achieving it was satisfying, and I know that that success will now allow me to do something more. It may be in swimming or another adventure—I don’t know yet…… Until then I’ll be thinking about what’s next, and beginning to work toward it.” p. 322-323.

Citations:

Cox, Lynn. (2004). Swimming to Antarctica: Tales of a long-distance swimmer. NY: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 322-323.

DeMont, Rick. 2001. “Freestyle Technique.” In The Swim Coaching Bible. Ed. Dick Hannula and Nort Thornton. Human Kinetics Press. Champaign, IL P. 140

Dweck, Carol. (2006). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. N.Y.: Ballantine Books.

Dweck, Carol. (2009). Mindsets: Developing talent through a growth mindset. . USOC Olympic Coach E-Magazine. http://coaching.usolympicteam.com/coaching/kpub.nsf/v/21feb09

Ericsson, K. Anders, Krampe, Ralf Th.,& Tesch-Romer, Clemens.(1993). The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance. Psychological Review, 100(3): 363-406.

Farley, Tom. (2008). Game On: How the Pressure to Win at All Costs Endangers Youth Sports and What Parents Can Do About It. ESPN Books.

Sternberg, Robert. (2005), “Intelligence, Competence, and Expertise.” In Andrew Elliot and Carol S. Dweck (eds.), The Handbook of Competence and Motivation. New York: Guilford Press.

THANKS: Many people contributed their ideas, critiques, and editorial help to putting together this article. Deborah Allen (my psychologist wife), Stevie Schein (University of Illinois Laboratory HS Swimming and Department of Psychology…my co-coach/daughter), Erin Hurley (Grinnell College Swimming), Cindy Jones (Fenwick H.S. Swimming, Oak Park, Il), Dee Dlugonski (University of Illinois, Department of Kinesiology), Ray Essick (USA Swimming).